Even before the pandemic began, more people here were dying at younger ages in the US than in other wealthy nations. A lot more.

In an article in the latest issue of the Atlantic, Ed Jong describes the result of a study by Jacob Bor, an epidemiologist at Boston University School of Public Health, using data from an international mortality database and the CDC. “For every year from 1933 to 2021, they compared America’s mortality rates with the average of Canada, Japan, and 16 Western European nations (adjusting for age and population).” They concluded that, starting in the 1980s the mortality rate in the US exceeded that of the average of other wealthy countries and that gap has been increasing ever since. They termed the excess deaths as “missing Americans”.

“By 2019, the number of missing Americans had grown to 626,000. After COVID arrived, that statistic ballooned even further—to 992,000 in 2020, and to 1.1 million in 2021. Were the U.S. ‘just average compared to other wealthy countries, not even the best performer, fully a third of all deaths last year would have been prevented.’ That includes half of all deaths among working-age adults.”

The U.S. had the worst COVID outbreak in the industrialized world—not just because of what the Trump did or didn’t do, but also because of fact that our whole economic and political system is failing to meet people’s needs, with healthcare being the most dramatic example. “COVID simply did more of what life in America has excelled at for decades: killing Americans in unusually large numbers, and at unusually young ages.”

We know that American’s life expectancy has been lower other comparable countries since the 1970s. By 2010, that gap was 1.9 years; by the end of 2021, it had grown to 5.3 years. Many countries took a longevity hit because of COVID, but the US was once again exceptional. It experienced the biggest decline in 2020, but unlike its peers, that decline continued in 2021.

So, what’s the big deal if I die at 76 versus 78? Think again. The fact is that our life expectancy is falling behind other wealthy nations in large part because a lot of Americans are dying very young—in their 40s and 50s, rather than their 70s and 80s. “During the pandemic, half of the U.S.’s excess deaths—the missing Americans—were under 65 years old. Even though working-age Americans were less likely to die of COVID than older Americans, they fared considerably worse than similarly aged people in other countries. From 2019 to 2021, the number of working-age Americans who died increased by 233,000—and nine in 10 of those deaths wouldn’t have happened if the U.S. had mortality rates on par with its peers.”

The crisis of early death was evident well before COVID. “Midlife ages are where health and survival in the U.S. really go off the rails. The U.S. actually does well at keeping people alive once they’re really old, (credit Social Security and Medicare, both are which are targets of the right) but it struggles to get its citizens to that point. They might die because of gun violence, car accidents, or heart disease and other metabolic disorders, or drug overdoses, suicides, and other deaths of despair. In all of these, the U.S. does worse than most equivalent countries, both by failing to address these problems directly and by leaving people more vulnerable to them to begin with.”

The origin of this mortality crisis goes beyond the fact that the US remains the only major wealthy country without universal health care. Further, we should note that the beginning of the mortality crisis corresponds directly to the triumph of neoliberalism and the rise of runaway inequality in the 1970s and 1980s. During this period the social safety net (as inadequate as it was) was progressively shredded; the public-health system languished after decades of underinvestment – with both factors tying health more closely to personal wealth and secure employment. As labor unions declined and minimum wages stagnated, more Americans had fewer resources to lean on if their health declined.

When the pandemic hit, poorer Americans already lived, on average, shorter lives than rich ones, and that gulf was widening. During the pandemic poor and minority groups were more likely to be infected because they lived in crowded housing, distrusted medical leaders, and couldn’t work from home or take time off when sick. And instead of addressing these foundational problems, policy makers focused on “personal responsibility”.

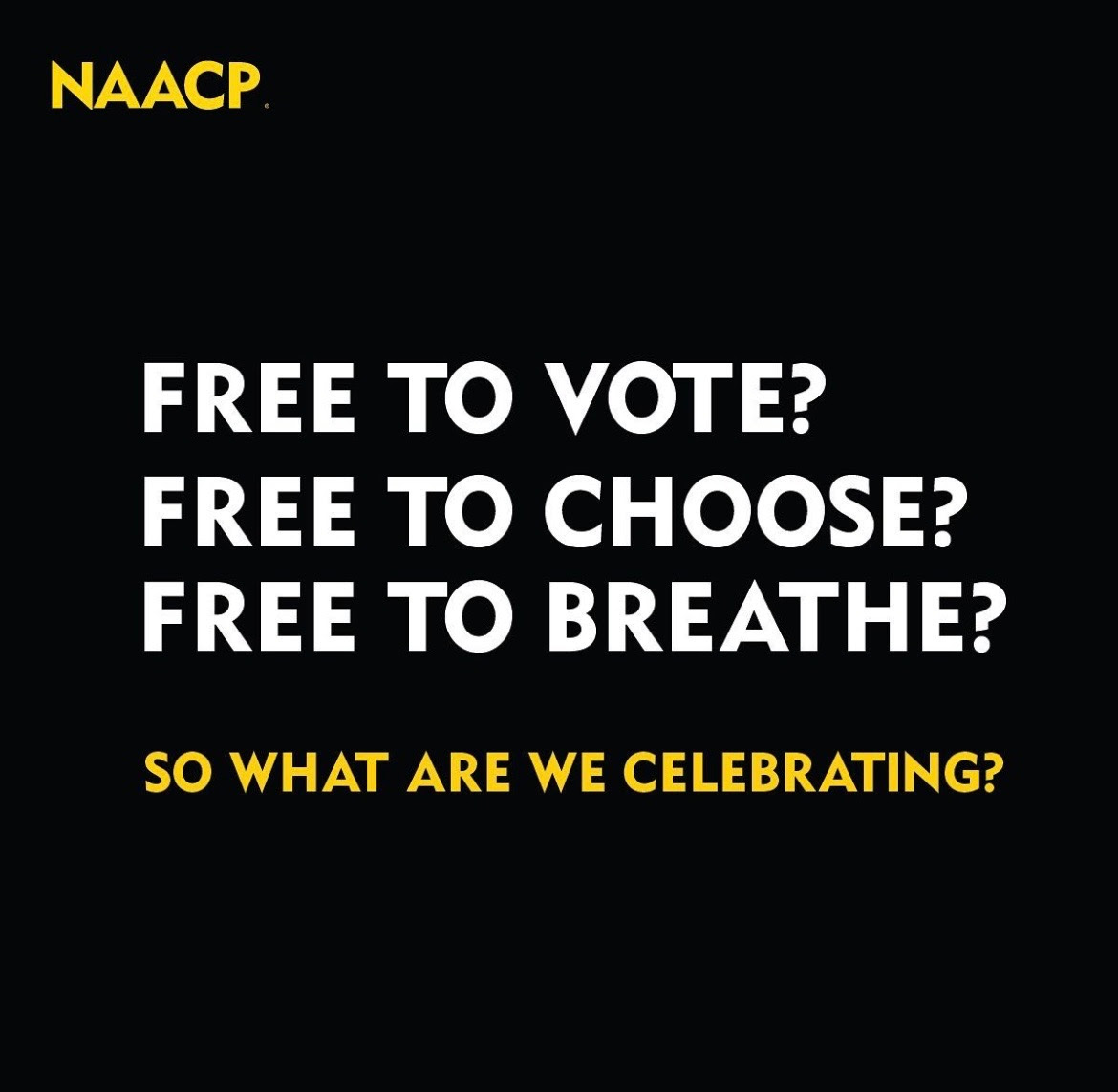

To sum up, the report could have had a subtitle, “Inequality Kills”, or perhaps “Neoliberalism Kills”. Due to the history of systemic racism and the widening divide between the haves and have nots our society kills Black, Brown, Indigenous and poor whites at a much higher rate than well-to-do whites. Unless we, as a society, recognize this fact, our solutions will continue to fall far short. The irony here is that, in the end, that failure (like the failure to deal with the climate crisis) will affect us all.

We may not all be in the same boat, but we are in the

same storm and, in the end, a tidal wave will sink even the biggest yacht.